The very last job to do on every new Rolls Royce that is built is done by hand.

This is done by a craft which was about long before the motor car ever came into production. The pinstripe or coach lines as it was called, which runs along both sides of a new Rolls Royce are painted on by hand.

Today it’s a symbol of quality and uncompromising craftsmanship.

Tommy Doherty had a small job any weekend he got a chance to get home from college. A local business near his new home on the High Rd. in Letterkenny would put his orders past for him until he would make the long journey home from Maynooth every so often.

Tommy Doherty’s father, John and his uncle Hugh were coach-builders in Ramelton, that’s where Tommy was born in 1903. They were coach-builders in one of the main towns in Donegal at the time. Tommy’s father John specialised in the coach-painting and design paintwork of the coaches which were hand-built by his uncle Hugh in their family business.

Tommy’s father hand-painted the coaches, which was a very specialised job. It included the hand painting of the pinstripes with a small specially trimmed squirrel hair paint brush. These horse-drawn coaches and carriages and traps were coming to the end of an era as steam and petrol were taking over from the horsepower in the form of trains and cars.

Tommy followed in his father’s brush strokes on his breaks home from college and was in demand as a specialised painter for number plates which were painted by hand for the rising amount of cars that were registering on the road of Co. Donegal.

That was nearly 100 years ago. This young part-time artist was also on his vocation to the priesthood. Tommy Doherty lived in Mc Clure’s Terrace in Letterkenny. It was Mc Cauley’s Garage then on the High Rd. who had the number plate orders ready for Tommy on his arrival home from Maynooth.

In those days with the roads so bad (nothing new there), number plates which were sitting exposed on the outside of mudguards were always getting damaged or knocked off. Tommy was getting a couple of shillings for each set of number plates he painted by hand.

Lucky White Heather

Tommy Doherty’s neighbour Jimmy Deeney who was originally from Derry also came to live in McClures Terrace in Letterkenny. Jimmy Deeney was one of the train drivers on the Londonderry & Lough Swilly Railway Line. When Jimmy Deeney moved from Derry to take up the job as a train driver with Lough Swilly Railway he had to first live at the end of the line in Burtonport.

Jimmy, Miah and Tommy, sons of the Lough Swilly train driver, Jimmy Deeney who moved to Letterkenny from Derry with the arrival of Letterkenny to Burtonport extension rail line.

He had to be available to hall the fish catches to market as soon as they were landed in Burtonport, where they were processed, salted and transported by train through to Derry. Later Jimmy moved to live in Letterkenny.

It was considered lucky to find white heather in them days and Jimmy Deeney was able to locate this lucky heather along the railway line high in the hills near Barnes Lower Gap.

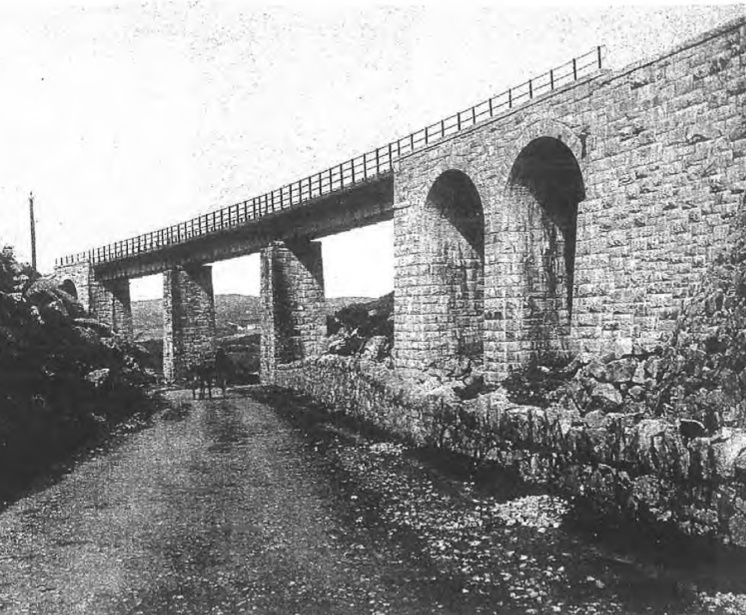

The viaduct in Barnes Lower when it was first built for the Letterkenny to Burtonport line.

Jimmy would give Tommy Doherty a couple of sprigs of white heather which Tommy would wear in the buttonhole of his coat. When Tommy returned to college in Maynooth he was the centre of attention with his white heather which was both good luck and good looking like himself as Tommy described it.

What Jimmy Deeney didn’t know or never said was that when Tommy Doherty was younger he would use the train like the wild west for cowboys and Indians. Tommy and the boys from the town would board one of the goods carriages on the train as a dare as it steamed out of the town and would get off it when it would stop out about Foxhall, Pluck or Manorcunningham station and would walk back to Letterkenny.

One such evening they decided to go on this adventure and ended up in the Royal Irish Constabulary Barracks in Dunfanaghy. Tommy wasn’t arrested that night and was told by the constable in charge to go home. Tommy would have gladly gone home if he knew what direction his home was or what town he actually was in!

So a frightened Tommy Doherty spent the night in a hedge in a garden next door to the barracks in Dunfanghy and waited all night to the following morning when some of the boys from Letterkenny were released and they all made their way home, but not on the train, this time!

It is twenty years ago this year back in 1997 that Archdeacon Tommy Doherty was at the Nazareth House in Fahan when he told us of his memories of his life growing up in Letterkenny.

Tommy recalled his memories of Letterkenny going for the Telegraph newspaper every morning before school for Cardinal O’Donnell and going for stamps and stationery and posting letters in the evening for the bishop and the priests in the Parochial House.

Cardinal Patrick O’Donnell, Primate of All Ireland who Fr. Tommy Doherty delivered the Telegraph newspaper to every morning as a young boy growing up in Letterkenny.

Years after his studies in Maynooth Tommy Doherty was ordained and was posted to Greenock in Scotland before returning to Donegal to take up a parish near Dungloe called Meenacross. Fr. Tommy Doherty brought a projector, some film and a camera home from Scotland which he used to record the happenings around his parish.

Fr. Tommy recorded a lot a happy occasions on his movie camera locally which he would show in the local hall which drew big crowds to see themselves on the big screen. Tommy also documented the closing of the Railway between Letterkenny and Burtonport in 1941.

Fr. Tommy Doherty was about to film the end of the railway in Donegal as it started to withdraw from the outer reaches. When it came to recording the train on its last journey from Burtonport he decided he was going to focus on the train heading down through Barnes Gap as the highlight of the documentary.

Fr Tommy had to think about what his final picture was going to look like before he shot it. In them days things were very tight. Fr. Tommy had to divide the little amount of cash he had between buying the film, sending it off to get processed and money for petrol for the car that his parishioners from Meenacross kindly bought for him. What few shillings that were left went on Woodbine cigarettes! They were needed as well, he joked!

Extras-Extras

Fr Tommy tried to think of everything for his filming of the final journey of the Letterkenny to Burtonport train. Fr. Tommy even asked the manager of the Cope in Dungloe would he release some of the staff from their duties for the day to be filmed as extras on the train in the event there wouldn’t be passengers on the final train journey.

Fr Tommy and the workers headed for Letterkenny on the back of the Cope lorry. The workers went up as far as Termon and Letterkenny and Fr. Tommy Doherty started filming on the way back down from Termon Station.

The Big Shoot

Ideally, Tommy would loved to have filmed the journey with two movie cameras but he only had the one camera and he only had a limited amount of expensive film. Tommy carefully positioned himself where he could film both the driver and the passengers in front of him and behind him on the train when the track would come to a curve on the line. He had the driver rehearsed to look out from the window of the engine as the train made its way through Barnes Gap.

The Cope lorry filmed from the Lough Swilly train captured by Fr. Tommy Doherty as it passed the small cottage in Barnes Gap.

Fr. Tommy captured the Cope Lorry racing alongside the train loaded up on the way back from Letterkenny, The driver of the lorry who was also encouraged to look over in the direction of movie camera as Fr. Tommy brilliantly established the location by including the small house in the middle of Barnes Gap before the train ascended high into the hills to pass over the viaduct as the cope lorry passed on the road below. In them days Fr Tommy had to wait for a couple of weeks before the processed film return to see if he managed to film what he set out to do.

The line filmed that day closed in Burtonport but with the Second World War and the shortage of coal and public pressure the line was reopened down as far as Gweedore Station to draw turf into Letterkenny and Derry.

That’s Deeney driving!

Hugh McGinley who still lives at Barnes Halt gatehouse which is on the Termon side of Barnes Gap where the old line crossed the N56 still remembers the train coming up from Gweedore as if it was yesterday.

As a young boy he could tell from the smoke and steam from the engine who was driving the train long before it got as far as the level crossing. In them days during World War 2 the train was fired with turf from Gweedore and anything else they could burn to produce power instead of the so-called clean burning coal of them days.

When the train was coming up from Cresslough the engine drivers knew there was no longer a stop at Barnes Halt. John recalled one of the train drivers, Jimmy Deeney who used the momentum to its best on the way up the hill as soon as he crossed over the Owencarrow viaduct as he headed into the gap.

John remembers the steam from the engine in Barnes Gap when Jimmy Deeney was at the controls. Jimmy never lifted on the way through the junction and the small family gate house seem to come alive as the train blasted through the level junction. The softness of the ground at the gatehouse meant that the train which weighed up to 59 tonnes alone plus 1,500 gallons of water, four tonnes of coal or turf and its carriages would rattle every cup and saucer and loose pane of glass as it went through the Junction at a top speed of 26 MPH, on a good day.

Fr. Tommy was promoted to Cannon and then Archdeacon throughout his vocation as a priest in Donegal, his last posting was to the parish of Dunfanaghy where he now was made a lot more welcome than the night he arrived unannounced by train all then years before.

Archdeacon Tommy Doherty passed away in 1998 and is buried in the grounds of St. Eunan’s Cathedral. His final resting place is just yards away from the old victorian post box which is still in operation to this day located in the old stonewall where a young Tommy Doherty posted the letters over 100 years ago.

The old Victorian post box in Letterkenny still in use where a young Tommy Doherty posted letter for Cardinal O’Donnell over 100 years ago. Photo Brian McDaid

Happy motoring folks

Tags: